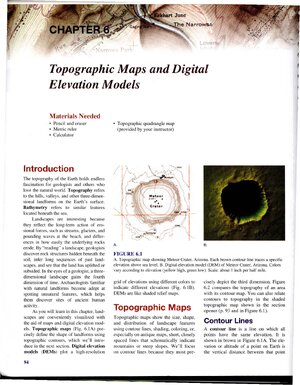

This document Iconography delves into the theory and significance of iconography in cartography, exploring how images and decorations on maps were perceived during the 18th century. Through historical perspectives and insights from renowned figures like Jean François, it highlights the role of iconography as both a decorative element and an instructional tool in mapmaking. By examining the intersection of art and geography, this document sheds light on how visual representations on maps conveyed geographical information and enhanced the viewer’s understanding. Discover the intricate relationship between decoration, symbolism, and practicality in the world of cartography through the lens of iconography.