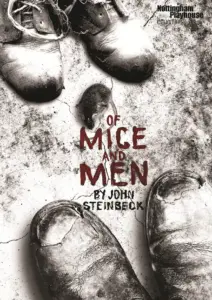

Of Mice & Men Education Pack

Uploaded by: nuniuniuh2

Report This Content

Copyright infringement

If you are the copyright owner of this document or someone authorized to act on a copyright owner’s behalf, please use the DMCA form to report infringement.

Report an issue