Topographic Maps and Digital Elevation Models

Materials Needed • Pencil and eraser • Topographic quadrangle map • Metric ruler (provided by your instructor) • Calculator

Introduction The topography of the Earth holds endless fascination for geologists and others who love the natural world. Topography refers to the hills, valleys, and other three-dimen- sional landforms on the Earth’s surface.

Bathymetry refers to similar features located beneath the sea.

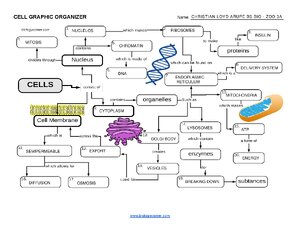

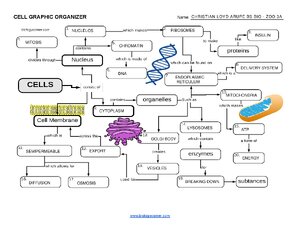

Landscapes are interesting because they reflect the long-term action of ero- sional forces, such as streams, glaciers, and pounding waves at the beach, and differ- ences in how easily the underlying rocks A. B. erode. By “reading” a landscape, geologists discover rock structures hidden beneath the FIGURE 6.1 soil, infer long sequences of past land- A. Topographic map showing Meteor Crater, Arizona.

Each brown contour line traces a specific scapes, and see that the land has uplifted or elevation above sea level. B. Digital elevation model (DEM) of Meteor Crater, Arizona. Colors subsided. In the eyes of a geologist, a three- vary according to elevation (yellow high, green low). Scale: about I inch per half mile. dimensional landscape gains the fourth dimension of time.

Archaeologists familiar grid of elevations using different colors to cisely depict the third dimension. Figure with natural landforms become adept at indicate different elevations (Fig. 6.1B). 6.2 compares the topography of an area spotting unnatural features, which helps DEMs are like shaded relief maps. with its contour map.

You can also relate them discover sites of ancient human contours to topography in the shaded activity. topographic map shown in the section As you will learn in this chapter, land- Topographic Maps opener (p. 93 and in Figure 6.1). scapes are conveniently visualized with Topographic maps show the size, shape, the aid of maps and digital elevation mod- and distribution of landscape features Contour Lines els.

Topographic maps (Fig. 6.1A) pre- using contour lines, shading, coloring, or, A contour line is a line on which all cisely define the shape of landforms using especially on antique maps, short, closely points have the same elevation. It is topographic contours, which we’ll intro- spaced lines that schematically indicate shown in brown in Figure 6.1 A. The ele- duce in the next section.

Digital elevation mountains or steep slopes. We’ll focus vation or altitude of a point on Earth is models (DEMs) plot a high-resolution on contour lines because they most pre- the vertical distance between that point

94

Chapter 6 Topographic Maps and Digital Elevaton Models 95

Normal closed contour has same elevation as Depression contour higher contour. has same elevation as lower contour.

200-foot contour

FIGURE 6.3 A normal closed contour (above left) encircles a small hill top. If this small hill is on the side of a larger hill, the elevation of the closed contour is the same as the higher contour, as shown here.

A depression contour (above right) encircles a pit or depression in the landscape. If the depression occurs on a slope, as shown, the depression contour has the same elevation as the lower contour. With a C.I. of 10 feet, the elevation of the inner depression contour is Shoreline = zero-foot contour 90 feet. The bottom of the depression is less

than 90 feet and more than 80 feet (because there is no 80-foot contour).

FIGURE 6.2 The area sketched in the top diagram is shown as a topographic (contour) map in the bottom diagram. Contour lines (brown) on the map are drawn at intervals of 20 feet, starting with 0 at mean sea level. The fact that contours bend upstream where they cross streams allows quick recognition of hilltops. Source: U.S. Geological Survey.

and sea level, which by definition has an pher wishes to show and the range of ele- They generally encircle small depressions, elevation of zero. Figure 6.2 shows an vation, or relief, of the mapped area. but can be used for large depressions (e.g., area along a sea coast, with the sea at its Florida is so flat that a 5-foot contour Fig. 6.1). average elevation of zero feet.

Because interval often best captures the landscape. the edge of the shore is everywhere at an The Rocky Mountains, on the other hand, Contour Line elevation of zero feet, the shoreline coin- show up best with lOa-foot contours. A Characteristics cides with the zero foot contour.

If sea 5-foot interval would paint a Rockies The construction and reading of contour level rose by 100 feet, the shoreline map solid brown with over-abundant maps are governed by the following char- would everywhere coincide with the contours’ acteristics of contour lines (most of which lOa-foot contour shown in Figure 6.2; if are illustrated in Figure 6.2): it rose 200 feet, it would coincide with Index Contours

the 200-foot contour. I. Every point on the same contour line As a general rule, every fifth contour has the same elevation. starting from sea level is an index con- Contour Interval tour. These are drawn as heavy lines and 2.

A contour line always rejoins or Contour lines are drawn on a map at labeled with their elevations (Fig. 6.2). closes upon itself to form a loop. evenly spaced intervals of elevation. The They make it easier to read a topographic This may occur outside the map difference in elevation between two con- map. Contours between index contours area.

Thus, if you walked along a secutive contours on the same slope is are usually not labeled. contour, you would eventually get called the contour interval (C.I.). It is a back to your starting point. constant for a given map, unless other- Depression Contours 3. Contour lines never merge, split, or wise stated, and is usually given at the Depression contours are closed contours cross one another.

However, if there bottom of the map. with hachures (Sh0l1 lines perpendicular to is a steep cliff, they may appear to The choice of contour interval de- the contour line) pointing toward the lower overlap because they are superim- pends on the level of detail the topogra- elevations within a depression (Fig. 6.3). posed on one another.

— – -~ -~ ——-=–…::~~—~~~…::==—~– —~- ———–

96 Part III Maps and Images

4. Slopes rise or descend at right angles to any contour line. • Closely spaced contours indicate a steep slope. • Widely spaced contours indicate a gentle slope. • Evenly spaced contours indicate a uniform slope. ~———-200— • Unevenly spaced contours indicate c.. = 20 feet a variable or irregular slope. 5. Contours usually encircle a hilltop.

FIGURE 6.4 If the hill falls within the map area, Reading elevations from a contour map with a contour interval of 20 feet. The elevation of X is the high point will be inside the 240 feet, because X falls on a contour with that elevation. Point Y falls between the 240- and 260-foot contours, so its elevation must be between those values.

Its horizontal position is about innermost contour (however, see three-quarters of the way between the two, so assuming a uniform slope gives an estimated discussion of depression contours). elevation of 255 feet. Point Y has a halfway elevation of 250 ± 10 feet: 250 is halfway between 6.

Contour lines near ridge tops or 240 and 260, and ± 10 indicates that Y falls between 240 (250 – J 0) and 260 (250 + 10). Note valley bottoms always occur in pairs that the error term (± 10) is found by dividing the contour interval by two. What is the halfway having the same elevation on either elevation of Z at the top of the hill? (Answer: 310 ± 10 feet) side of the ridge or valley. 7.

Contours always bend upstream uniform, so another approach is to give the DEMs make it easier to visualize when they cross valleys. Because halfway elevation between the two con- landscapes, and they often highlight sub- water runs downhill, this fact allows tours.

A halfway elevation is the elevation tle features that are not obvious on topo- the rapid recognition of high and low halfway between the values of adjacent graphic maps. However, unless you have areas on a contour map. contours; thus, the elevation of a point a computer handy, topographic maps are 8.

If two adjacent contour lines have between contours can be stated as the more useful in the field because it is the same elevation, a change in slope halfway elevation plus or minus one-half easier to read accurate elevations, spot occurs between them. For example, the contour interval.

Figure 6.4 provides places that are easier or more challenging adjacent contours with the same examples. to hike over, and find such human- elevation would be found on both Study of Figure 6.3 shows that a nor- designed cultural features as roads, sides of a valley bottom or ridge top. mal closed contour that lies between a buildings, dams, and political boundaries. 9.

Depression contours have the same higher and a lower contour always takes If you have access to Geographic Infor- elevations as the normal the same elevation as the higher one.

A mation System (GIS) software, you can (unhachured) contours immediately depression contour in the same situation drape (superimpose) a variety of topo- downhill (Fig. 6.3). always takes the same elevation as the graphic map features over your DEM to lower one. get the best of both worlds.

Reading Elevations Start with a labeled index contour. As you Digital Elevation Working with Maps move uphill from this contour, keep track of the elevation by adding the value of the Models We have to cover a few “necessary contour interval for every contour crossed.

A digital elevation model (DEM) con- evils” before we can dive into land- In Figure 6.4, moving from the 200′ index sists of a high-resolution grid of points scapes and topographic maps. Coordi- contour to point X crosses two contours: assigned elevations and colored accord- nate systems are important because they 200′ + 20′ + 20′ = 240′ elevation. When ing to elevation (Fig. 6.1 B).

Most DEMs allow us to precisely locate points on hiking downhill you subtract contour are compiled from existing topographic the Earth’s surface. We also must intervals. maps. However, radar data from the understand the scale of a map so we can The elevation of a point that does not Space Shuttle (SRTM), specially com- tell how big things are. For example, the fall on a contour must be estimated.

An missioned aircraft flights, and data from scale of the map in Figure 6.1 A tells us estimate can be made by interpolation, various satellites are processed to provide that Meteor Crater is about I ~ miles assuming the slope between adjacent con- higher-resolution DEMs than are other- across and not 50 miles across. Coordi- tours is uniform.

For example, a point one- wise available from such government nate systems and scale are not difficult quarter of the way between contours with agencies as the U.S.

Geological Survey, to understand once you get used to elevations of 200 and 220 feet (C.l. = 20 the Centre for Topographic Information them, but they will take some extra con- feet) would have an elevation of about (Natural Resources Canada), and INEGI centration as you read the next few sec- 205 feet. However, slopes are often not in Mexico. tions. Understanding these concepts is

Chapter 6 Topographic Maps and Digital Elevaton Models 97

also important if you plan on taking a GIS class in the future.

Map Coordinates and Land m <0 o

Subdivision f+;+-+-‘-+-+—-‘-+—+–I’-‘–+–+-+I

Coordinate systems provide a permanent Equator way of describing locations. For example, older descriptions of mineral or fossil sites commonly refer to landmarks. Unfortu- nately, some of these old sites are now lost because road intersections, houses, small bridges, old trees, and railway lines have A. B. since been moved or removed due to

FIGURE 6.5 ongoing development. A coordinate sys- A. Cutaway view of the Earth. The east-west line 40° north of the equator is latitude 40° N; the tem allows a state to efficiently and penna- north-south line 50° west of the prime meridian is longitude 50° W. B.

Lines of latitude parallel nently keep track of the locations of aban- the Earth’s equator, while lines of longitude intersect at north and south geographic poles. The doned oil wells, toxic waste sites, sealed shaded area, bounded by lines of latitude and longitude, is a quadrangle. mine shafts, and places hosting endan- gered plants or breeding pairs.

It allows geologists to describe important rock 30″N, longitude 132° 15′ 45″W). By con-

Figure 6.5A. A longitude line 50° west of localities, and it allows hikers to precisely vention, latitude (north-south) is given the Prime Meridian is termed 50° W; one locate trailheads, remote camp sites, and 90° east of the Prime Meridian, or one- first, longitude (east-west) second. other places worth remembering. Minutes and seconds are often ex- quarter the way around the globe, is 90° E.

The east and west meridians meet pressed as decimal equivalents of a degree Latitude-Longitude at 180° on the opposite side of the planet. on global positioning system (GPS) re- System The 180° meridian corresponds to the ceivers and in computer applications.

A The most well-known global coordinate International Date Line, except for where latitude of 43° 5′ 8″, for example, can be system is based on east-west lines called the date line shifts to avoid causing time- converted to a decimal as follows: 5′ = lines of latitude and north-south lines zone problems in islands or island groups 5/60th of a degree or 0.083°, and 8″ = called lines of longitude. cut by the 180° line.

The latitude and lon- 8/3600th of a degree = 0.002° (there are Latitude measures distance north or gitude lines make a single grid network 60 X 60 = 3600 seconds in a degree). south of the equator. The lines of latitude, that covers the entire globe (Fig. 6.5B).

Thus, 43° 5′ 8″ = 43° + 0.083° + also called parallels, form a series of par- The measurement of angles from 0.002° = 43.085°. allel circles running east-west (horizon- the equator (latitude) and from the The U.S. Geological Survey (USGS), tally) around the globe. The equator rep- Prime Meridian (longitude) is most Centre for Topographic Information resents the 0° latitude line.

Other parallels commonly done in degrees (symbol 0). (Canada), and INEGI (Mexico) have are set at angular intervals measured A circle is divided into 360°. One made most of the accurate maps of their north or south of the equator, as shown in degree is divided into 60 minutes (60′), respective countries. These maps are

Figure 6.5A. A latitude line 40° north of and each minute into 60 seconds (60″). commonly bounded by latitudes and lon- the eq uator is termed 40° N.

The geo- Maps also may indicate angular mea- gitudes, both of which are usually sepa- graphic poles are at 90° and 90° S. surements in mils (one mil = 1/6400 of rated by intervals of 1°, 12° (= 30′), XO Longitude measures distance east or 360°, or 0.05625°). When measured on (15′), or (in the United States) ~o OW). west of the Prime Meridian.

Lines of lon- the Earth’s surface, one degree of lati- Such maps cover rectangular-shaped gitude, also termed meridians, form a tude (as measured along a meridian) is areas called quadrangles (Fig. 6.5B), series of circles running north-south (ver- approximately III km (69 miles), and which are generally named after the tically) and intersecting at the geographic one degree of longitude (as measured largest town or most promjnent geograph- poles.

The Prime Meridian is the north- along a parallel) varies from about ic feature in the area (for example, the south line passing through the Royal II I km at the equator to 0 km at the Mt. Shasta, California 7Y2′ Quadrangle). Observatory in Greenwich, England; it is poles, where the meridians intersect. The numerical values of the latitudinal defined as 0° longitude.

The other meridi- A point on a map can be located by and longitudinal boundaries are given on ans are set at angular intervals east or referring to the latitude and longitude of each map corner; intermediate values are west of the Prime Meridian, as shown in the point (for example, latitude 43° 5′ indicated on the map margins (Fig. 6.6).

( ,J r 1–‘ _ J C’ i21″.. 860 )/1:925 . ‘V !.Y U (r ) _ _ ~ 936

/ B~ II N-r/ eRE E K J

I t././ -‘ -‘

T 114 N

T 113 N

—-”—-‘-~ ~”__’___t’_—-‘L—-‘—-‘-L—-‘–‘—~-JU..L—–‘–LL’—‘~—–”-‘–L.~-==”’–~., -44°37′ 30″ • INTERIOR-GEOLOGICAL SURVEY RESTON V1AGtN1A-1982 93037’30” ’50 00om E

FIGURE 6.6 This corner of a quadrangle map shows the latitLIde and longitude of its southern and eastern boundaries, UTM grid coordinates, and township and range designations (red). The UTM grid is shown with thin black lines. Along the side, 4945 is shorthand for 4,945,000 mN and 49 43 000 mN for 4,943,000 mN.

Similarly. along the bottom, 4 48 is shorthand for 448,000 mE and 4 50000 mE for 450,000 mE. On a full-sized map, the zone number is found in the lower left corner in the fine print. This map falls within zone 15.

UTM example: A given house (small black square) falls within a 1000-m square defined by grid lines 4,942,000 mN (south side), 4,943,000 mN (north), 449,000 mE (west), and 450,000 mE (east). To determine its coordinates, measure in millimeters the distance from the 4,942,000 mN line to the house and then the total distance to the 4,943,000 mN line.

The house is located 39 mm out of a total 42 mm between grid lines. [n percent, 39/42 = 0.93 or 93%. Since the grid distance represents 1000 m, the house is located 0.93 X 1000 = 930 m above the southern line, or at 4,942,930 mN. Similarly, the house is located 20 mm/42 mm or 48% of the way east of the 449,000 mE line. This equals 449,480 mE.

The location of the house, to within a 10-m square, is formally given as: 4,942.930 mN; 449,480 mE; Zone 15; northern hemisphere.

98

Chapter 6 Topographic Maps and Digital Elevaton Models 99

96″ 95″ 94″ 93″ 92″ 91″ 90″ W

5,400,000 mN

48°N -rt-+–++–+—4+–+–t-r-~ 5,300,000 mN

-+-+-+–+1–+–++–+-+-+ 5,200,000 mN

+-+–+—++–1–++–+-+-+ 5,100,000 mN

+-+-+–I-I–+—+t—-+—+–+ 5,000,000 mN

44°N -~:t:t=:=+t==t:=:tt:=~:::t:4,900,000 mN

! I … ~r’–, ;-, lambert Equal Area Projection II I I ‘ ! , w w w J.J ~ ‘w A. E E E E E E o ,8 o 10 o 8 8 § g I~ /8 8 8 g co,1.0 8′ I’– ” (0

FIGURE 6.7 +-+–++—++–+—j-+—1-+-+-+- 400,000 mN A. UTM-grid zones in North America. Each zone is 6° of latitude wide. The zones are numbered counting west to east from the International Date Line. -+-+—1-j—+I—+—++–H–+–+- 300,000 mN At the middle of each zone is the central meridian used to set up the east-

west 1000-meter UTM grid lines. 2°N –=l:::t=ti=:tt:=::j::=~=t:t=::j:::t 200,000 mN B. Example showing two parts of the UTM grid for zone 15 (black lines).

The lines of latitude and longitude are in red. The grid system counts -+-+—1-+–++—+—++–H–+–+- 100,000 mN meters north of the equator and east or west of the central meridian, which is arbitrarily set to 500,000 meters. The lines on the two grids are parallel near the equator but not at higher latitudes because most latitude and longitude lines are projected as curves, whereas UTM lines are drawn as 91″ 90″ W straight lines on this projection. The point in the shaded area is located in

Figure 6.6.

Because the Earth is round, even small positioning system (GPS) units allow you to a value of 500,000 m to avoid coor- areas (like the shaded one in Fig. 6.5B) to switch between latitude-longitude and dinates with negative numbers (study represent curved surfaces that must be UTM coordinates. Fig.6.7B). shown on flat maps.

This requires a projec- The UTM system divides the 360° Features are located by their UTM tion of the three-dimensional curved sur- range of longitude into 60 north-south coordinates. UTM coordinates are given faces onto a two-dimensional sheet of zones, each 6° wide. Figure 6.7 A shows by distinctive numbers (e.g., 49 44°00, paper. Many ways have been developed to these zonc:s in North America.

The 4945) along the margins of USGS maps

accomplish this-names such as “Mercator zones are numbered from west to east, (Fig. 6.6). The numbers give the distance projection” or “polyconic projection” may beginning at the International Date in meters from the zone origin. In Figure be familiar to you-but all unavoidably Line.

The zone number is given in fine 6.6, for example, 4943°00 mN describes an result in some sort of distortion and create print in the lower left corner of USGS east-west line 4,943,000 m (4943 km) certain difficulties. quadrangle maps. Each zone is divided north of the equator. The east-west line into a grid with its origin at the inter- I km (1000 m) to the north is 49 44°00 mN.

Universal Transverse section of the equator and its own The larger “44” makes it easier to count central meridian, as shown for zone IS the I-km increments. The complete UTM Mercator (UTM) in Figure 6.7B (e.g., 93° W is the cen- coordinate is given as: north-south coor- System tral meridian between 90° to 96°).

A dinate (northings), east-west coordinate A second widely used global coordinate metric grid, with lines intersecting at (eastings), zone number, and hemisphere grid is the UTM system. Its set-up may right angles, is developed from this ori- (north or south).

Because some give the seem somewhat complex, but the UTM gin on a transverse-Mercator-type map east-west coordinates first and the north- system produces a handy grid of I-km projection. Lines running east-west south coordinates second, it is essential to squares on many maps.

This makes it count the number of meters from the label your UTM coordinate numbers with easy to determine accurate grid coordi- equator. North-south lines measure the “mN” (meters north) and “mE” (meters nates from paper maps and to determine number of meters from their zone’s east). Figure 6.6 gives a worked example distances between points.

Most global central meridian, which is arbitrarily set determining UTM coordinates.

100 Part III Maps and Images

South miles. Political townships, usually named Dakota after the largest town within the area at the time they were designated (for exam- Wyoming Correction line ple, Baraboo Township, Wisconsin), may Nebraska or may not coincide with Public Land Base line Survey townships.

Tiers and ranges are numbered by ref- Colorado erence to the baseline and principal meri- Kansas }Tier 3S (T3S) dian (Fig. 6.8B). The first tier north of the A. baseline is Tier 1 North (abbreviated TIN); Correction one in the fifth tier to the north is T5N, and line so forth. Ranges are numbered to the east B. of the principal meridian (for example, R5E) and to the west (R2W).

A Public Land Survey township (like the shaded one in Fig. 6.8B) is located using tier-range R3E R4E R5E coordinates: T3S, R4E.

NOTE: Tier is 24 T2S always written first, range second. ~G 29 SE)4, NW)4, Sec. 16, T3S, R4E Because lines of longitude (meridi- 31 32 33 34 35 36 ans) converge toward the poles, it is 3 ?- /( 6 5 4 3 2 1 6 lE NW)4 impossible to maintain squares that are NW)4 6 miles on a side.

Thus, a correction is V 12 7 8 9 10 11 12 7 T3S , made at every fourth tier line (labeled cor- R4E -fa 18 17 16 15 14 13 18 T3S rection line on Fig. 6.8B), and new range ~ 24 19 20 21 I~ ~ 24 19 A

lines 6 miles apart are established. The ;::::-.. E~ 1″”- 25 30 29 28 27 26 § -?..> cOlTection restores townships immediately I~ 31 32 33 34 35 36 31 tt- north of the line to their proper size. :q 6 5 ~ 3 2 1 F Each 6-mile-square township is subdi- –¥ H 0 vided into thirty-six, 1- X I-mile squares, called sections, which are numbered in a T4S specific sequence (Fig. 6.8C). Each section C. D. consists of 640 acres. A section is subdi-

FIGURE 6.8 vided into halves, quarters, eighths, six- U.S. Public Land Survey subdivision, illustrated by successively smaller areas. A. Example of a teenths, and so on (Fig. 6.8D). A sixteenth baseline and principal meridian in the western United States. The area to which they apply is of a section is 40 acres. shaded. B.

From a starting point at the intersection of a principal meridian and a baseline, 6-mile- Points are located according to the wide tier and range bands subdivide land into 36-square-mile townships. C. Townships are smallest subdivision required. In Figure subdivided into 36 I-square-mile sections. D.

Sections can be divided into halves, quarters, 6.8D, the star is located, to the nearest eighths, or other fractions. 40 acres, in the SE )4, NW )4, Sec. 16, T3S, R4E. Locations are always written from the smallest unit to the largest, and u.s. Public Land The starting point for subdivision is the intersection of selected latitude and tier is written before range.

Survey System longitude lines. The starting latitude is the Section numbers and tier and range values are written in red on USGS topo- The U.S. Public Land Survey System was baseline, and the starting longitude is the graphic maps (see Fig. 6.6). designed to efficiently describe areas of principal meridian.

Baselines and prin- land in most states outside of the original cipal meridians are established for a num- 13 colonies. This system, commonly called the Township-Range system, was started in ber of areas in the United States; an example is shown in Figure 6.8A. Lines Map Scale

1785, when the old Northwest Tenitory drawn 6 miles apart and parallel to the The scale of a map is essential because it (Lake Superior region) was opened to baseline form east-west rows called tiers. tells the user the size of the area repre- homesteading.

It has been widely used for North-south lines parallel to the principal sented and the distance between various ordinary and legal land descriptions in the meridian and 6 miles apart form north- points. Three types of scales are in com- western two-thirds of the United States south columns called ranges (Fig. 6.8B). mon use: ratio, graphic, and verbal scales. ever since.

The method subdivides land The squares formed by the intersection of A ratio or fractional scale, shown at

into 6- X 6-mile squares called townships; tiers and ranges are called townships. the bottom of Figure 6.9, is the ratio these are further subdivided into 1- X Each township is approximately 6 miles between a distance on a map and the I-mile squares called sections. square and has an area of about 36 square actual distance on the ground. The ratio

U.S. Public Land Survey Range coordinate r Intermediate longitude (in minutes and seconds) r UTM coordinate (without zeros; kilometers east) MT. SHASTA QUADRANGLE CAUFORNIA — SISKIYOU CO. 7.5 MINUTE SERIES (TOPOGRAPHIC)

U.S. Public Land Survey tiercoo~

U.S. Public Land Survey ~ section number/’ –

StatePla~ coordin~t~” ~ number (not discussed)

Map data, including zone andUTM the …. ..-.s-“””‘-…… ‘_ ‘=.~~~”:.__ 101Xll _ V _ North American :2-=::?:::’-:7-_ _ ….:::-~.::.:.:=..-=.-_”‘;’;’ 1~ 11.5._. 8 13 =~—- – – – — Datum to use ~::.:::=E:.:::r=:-: . .L~~==:::;;:-“”””t__;::=:;::’~=~~::::’:’::~~=-_;:::±:;:=7″””rrl”‘T’J”T’J:~~ .__ 0 ::;”—- — in your GPS _=~:’::J::.:””‘:__~.

Contour • :::::..– :::-‘::~:-“”a ~ ==- FIGUR~e:~;er.. ~…:=;:…-::.::..-:.:==;=.- ,’,:-. “;”:: ~ interval • !~~~-::=C MT. S~A, CA ) “‘–J Reduced copy of the Mt.

Shasta, California, 7’/,- Magnetic declination (MN) Names of d I r- ,–..- adjoining—… ‘—–t–+—I~=– 6CllyofMt.Sh-. t minute quadrangle, with principal map features qua rang es ~~ Name of quadrangle highlighted and magnified. “””‘”””””. and year of publication

102 Part III Maps and Images

scale on Figure 6.9 is I:24,000 (or the ground. In general, the larger the area Example: Convert a fractional scale of

1124,000), which means that one unit (for shown, the smaller the scale of the map I:62,500 to a verbal scale of I map inch example, an inch) on the map equals (smaller because the fraction 1!500,000 is equals X miles on the ground. 24,000 of the same units on the ground. a smaller number than 1/12,000).

I. Units to be related are inches and A graphic scale usually consists of a scale bar subdivided into divisions corre- Converting Among miles. sponding to a mile or kilometer (see Fig. Scales 2. 1:62,500 = 1″/62,500″ 6.9). One mile or kilometer segment on 3.

Convert 62,500″ into miles by divid- the scale bar is commonly subdivided to Verbal to fractional scale ing by the number of inches in allow more precise measurements of dis- conversion: I mile. One mile = 5280 feet and tance. The subdivided units are commonly 1 foot = 12 inches. So, 1 mi = placed to the left of zero on a scale bar, as I. Convert map and ground distances 5280′ X 12″ = 63,360″.

Working in Figure 6.9. A graphic scale is helpful to the same units. out the division: because it is readily visualized and stays 2. Write the verbal scale as the fraction: 62,500 inches . in true proportion if the map is enlarged or ‘ I . = 0.986111/ Distance on map 63 ,360 mc 1es per 1111 reduced. It also provides a convenient way Distance on ground of measuring distances between points on 4.

Expressed verbally, I inch on the a map: lay a strip of paper between the 3. Divide both numerator and denomi- map equals 0.986 mile on the points and make pencil marks next to nator by the value of the numerator: ground. each point. Then lay the paper along the

Distance 0/1 map/distance on map graphic scale at the bottom of the map and Distance on ground/distance on map determine the distance. Magnetic Example: Convert the following verbal A verbal scale is commonly used to discuss maps but is rarely written on scale to a fractional scale: 2.5 inches on Declination them.

People usually say, “I inch equals the map represents 5000 feet on the Maps are usually drawn with north at I mile,” which means, “I inch on the map ground. the top. North on a map refers to true represents, or is proportional to, 1 mile geographic north. At most places on I.

Convert both map and ground dis- on the ground.” Because I mile equals Earth, however, a compass needle does tances to the same units, inches: 63,360 inches, a common fractional scale not point toward the geographic north

5000 X 12″ = 60,000″. The verbal

of 1:62,500 on older maps corresponds pole but toward the magnetic north pole. scale is now 2.5 inches on the map closely to the verbal scale “I inch to The magnetic north pole is in the

represents 60,000 inches on the I mile.” Many U.S. maps, and essentially Canadian Arctic, but its exact position ground. all foreign maps, use metric scales, mak- changes. For example, in 1955, it was ing common fractional scales easily con- 2.

Write the verbal scale as the fraction: located north of Prince of Wales Island vertible to verbal scales: scales of 2.5″ (distance on map) near latitude 74° N, longitude 100° W; I:50,000, I: 100000, and I:250,000 cor- 60,000″ (distance on ground) its last measured location in 200 I put it respond to I centimeter equaling 0.5, 1.0, in the Canadian Arctic Ocean (81.3° N,

and 2.5 kilometers, respectively. 3. Divide the numerator and denomina- 110.3° W) headed northwest toward 4° quadrangle maps are drawn at a tor by the value of the numerator: Siberia at 40 km/year. fractional scale of I: I,000,000; 2° quadran- 2.5″/2.5″ I The angular distance between true gles at I:500,000; I ° at I:250,000; 15′ at 60,000″/2.5″ 24,000 or 1:24,000 north and magnetic north is the mag- I:62,500 or I:50,000; and 7′.1.’ at 1:24,000 netic declination. Because the location

or 1:25,000. Both graphic and fractional Fractional to verbal scale of the magnetic pole changes, the mag- scales are shown at the bottom center of the netic declination generally varies with conversion: map (see Fig. 6.9). time. If you are navigating or doing geo- These different scales are used to I.

Select convenient map and ground logic research using a compass, you show larger or smaller areas of the Earth’s units to relate to each other (for must adjust the declination of the com- surface on conveniently sized maps. For example, inches and miles or cen- pass for local conditions.

Without example, it may be possible to show a timeters and kilometers). adjustment, compass errors in excess of small city on a map where I inch on the 10° to 20° are possible along the west 2. Express fractional scale using the map represents 12,000 inches (1000 ft) on and east coasts of North America! The map units (inches or centimeters). the ground.

This map would have a scale magnetic declination is shown at the of I: 12,000. However, to show a mid- 3. Convert the denominator to the bottom of most USGS maps by two sized state, such as Indiana, on a map of ground units (miles or kilometers). arrows (see Fig. 6.9). One points to true similar size, the scale would have to be 4.

Express verbally as “I inch [or north (commonly marked with a star, or much smaller, say I inch on the map to I centimeter] equals X miles [or T.N.) and one points toward magnetic 500,000 inches (approximately 8 miles) on kilometers].” north (commonly marked M.N.). The

Chapter 6 Topographic Maps and Digital Elevaton Models 103

angular separation between them (the precisely determined elevations used in the edge of the map.

Label each magnetic declination) also is given. the construction of topographic maps. contour or index contour with its When stating the magnetic declination They are shown at many section cor- elevation. of a map, it is always necessary to indi- ners, bridges, road intersections, hill- cate whether the arrow pointing to the tops, and the like and may be marked magnetic pole is east or west of the geo- with an “x” (examine Fig. 6.9).

Bench Topographic Profiles graphic pole. If it is east, the declination marks and spot elevations are used in A topographic profile shows the shape is stated as so many degrees east, for conjunction with aerial photographs to of the land surface as it would appear in a example, 212° E. Most maps also have construct topographic maps. Two aerial cross section; it is like a side view.

Topo- an arrow pointing toward G.N., the photos, taken from different points but graphic profiles portray the shape of the location of the grid north direction for overlapping the same area, provide a land surface along a particular line of pro- the Universal Transverse Mercator three-dimensional view of the land sur- file.

They are useful for many practical (UTM) grid system (see Fig. 6.9). face when viewed through a stereoscop- purposes, such as planning roads, rail- ic viewer.

By orienting the photos prop- roads, pipelines, hiking trails, and the Symbols erly, two beams of light from different like, or for estimating the volume of Standardized symbols and colors are used sources can be focused at any elevation. material that will need to be excavated or on government maps to designate various If the superimposed beams are moved filled during road construction.

Profiles features. On USGS maps, cultural fea- around a hill, for example, they will are most easily made along straight lines, tures (those made by people) are gener- trace a line at a precise elevation.

The but they can also follow curved paths, ally drawn in black; forests or woods are numerical value of this elevation can such as a road or a stream. shown in green (they are not always rep- be determined from known elevations A topographic profile is made from a resented); blue is used for bodies of within the area (e.g., bench marks).

Aer- contour map using the following proce- water; brown shows elevation (contours), ial photographs are discussed further in dure (Fig. 6.12): some mining operations, and beaches or Chapter 7. l.

Select the line or path along which sand areas; and red is used for the better If you are a landscaper or an archi- the profile is to be made, such as line roads and some land subdivision lines. tect, for example, you may want to make X-Y in Figure 6.l2A.

See Figure 6.10 for symbols and Figure your own detailed topographic map of an area. You can start by tracing any impor- 2. Record the elevations along the line 6.9 for some examples. Note that when tant features (drainages, coastlines, as shown in Figure 6.12B.

To do this, USGS topographic maps are revised, any buildings, etc.) from an air photo lay the straight edge of some scratch new features (e.g., roads, suburbs, strip mines) that appear in an area are colored obtained from the USGS or from your paper along the line of profile. Mark state. Then, starting from the lowest spot on the paper the ends of the profile purple.

Symbols for Canadian govern- ment maps are shown on the backs of the on the property, take a series of hikes line and the exact place where each maps. Mexican map symbols are gener- uphill with a 5-foot staff and a spirit contour line meets the edge of the ally on the front. (bubble) level that allows you to site paper.

Label each mark on the paper horizontal lines from the top of your with the elevation of the correspond- staff. These allow you to plot successive ing contour. Also mark the positions Working with elevation increments of 5′ on your map of any streams that cross the line of Topographic Maps (Fig. 6.l1A).

Now add the contours to profile, because they will be low points on the profile. reflect the landscape by following these Now that you understand contours, coor- steps: 3. Set up the graph on which the profile dinate systems, and scale, we are ready to will be drawn (Fig. 6.l2C). First note cover some ways of working with topo- I.

Select a contour interval that will the differences in elevation between graphic maps. We’ll start with the basics show the level of detail you need. the highest and lowest points along the of how topographic maps are produced. Too many contours can be confusing. line of profile; this will determine the 2. If your staff was a convenient length range of elevations on your profile.

Making Topographic (e.g., 5 feet), simply connect those Label the vertical axis with a range of Maps points that correspond to multiples elevations that extends beyond the Making a topographic map requires ac- of the contour interval. If the c.I. is profiJe elevations and conveniently curate points of elevation in the map 20 feet, you would connect dots allows each contour to be graphed. In area.

A bench mark is a point whose marking 20, 40, 60, etc., feet. Figure 6.l2C, the profile elevations elevation and location have been pre- 3.

Draw fairly smooth, fairly parallel range between 820 and 940 feet and cisely determined by government sur- contours, but be sure to bend them are spanned by a vertical axis of 700 veyors; its location is marked by a small upstream when crossing drainages to 1000 feet. Horizontal lines on the brass plate. Bench marks are designated and gullies (Fig. 6.l1B).

Adding vel1ical axis are 20 feet apart, which on maps by the symbol B.M. (Fig. 6.9). extra wiggles implies you know matches the contour intervaJ and Spot elevations are somewhat less- more than you do. Draw the lines to makes graphing simple. CommonJy,

Topographic Map Symbols BOUNDARIES RAILROADS AND RELATED FEATURES COASTAL FEATURES National. . . ….. _– Standard gauge single track; station.. Foreshore flat (shallow sediment). State or territorial _ Standard gauge multiple track . Rock or coral reef . County or equivalent. — Abandoned . Rock bare or awash .. Civil township or equivalent. …. . 1 – _ , _ Under construction .

Group of rocks bare or awash . Incorporated-eity or equivalent. . . .r- – – – – Narrow gauge single track . Exposed wreck ………………….•.. Park, reservation, or monument. .. . I– . _ Narrow gauge multiple track . Depth curve; sounding . Small park . Railroad in street. . Breakwater, pier, jetty, or wharf. Juxtaposition ……………………•. Seawall ..

LAND SURVEY SYSTEMS Roundhouse and turntable . U.S. Public Land Survey System: BATHYMETRIC FEATURES Township or range line. TRANSMISSION LINES AND PIPELINES Area exposed at mean low tide; sounding datum ._…../. Location doubtful. … f- _ _ _ Power transmission line: pole; tower.. Channel . Section line f—–j Telephone or telegraph line. Offshore oil or gas: well; platform . o •

Location doubtful. – – – Above-ground oil or gas pipeline. .~_ _~ Sunken rock. Found section corner; found closing corner I- ~ ~_ Underground oil or gas pipeline . Witness corner; meander corner ~c1+ _ ~ RIVERS, LAKES, AND CANALS I MC, CONTOURS Intermittent stream . . ….—. .

Other land surveys: Topographic: Intermittent river . . …. – ..:::::: Township or range line.

Section line. Intermediate . Disappearing stream. .. .. —< Index . Perennial stream. Land grant or mining claim; monument.. . …. +_ _ to Supplementary . Perennial river .

Fence line .. Depression .. Small falls; small rapids . Cut; fill .. I-.”~””;,.j Large falls; large rapids .

ROADS AND RELATED FEATURES Primary highway.. f—~ Bathymetric: Secondary highway.. Intermediate. Masonry dam . Light duty road. Index. Unimproved road. Primary..

Dam with lock. Trail. . Index Primary . Dual highway. Supplementary. Dual highway with median strip . Dam carrying road. Road under construction . ~_~ MINES AND CAVES Underpass; overpass.. .~ Quarry or open pit mine .

Intermittent lake or pond ,. Bridge . I-__~ Gravel, sand.. clay, or borrow pit. .

Dry lake .. Drawbridge. I-__~ Mine tunnel or cave entrance.

Narrow wash. Tunnel. . 1-0″””‘- Prospect; mine shaft. .

Wide wash . ‘,’ Mine dump ..

Canal, flume, or aqueduct with lock . BUILDINGS AND RELATED FEATURES Tailings .

Elevated aqueduct, flume, or conduit.

Dwelling or place of employment: small; large.. • _ Aqueduct tunnel. School; church. •• SURFACE FEATURES Water well; spring or seep . Barn, warehouse, etc.: small; large. 0 ~ Levee House omission tint. Sand or mud area, dunes, or shifting sand.

GLACIERS AND PERMANENT SNOWFIELDS Racetrack . . >’-<) Intricate surface area. ~~~~ Contours and limits. Airport. . . . . . . . . . . . . . .. .. . . . .. .. .. . C::-.'–", Gravel beach or glacial moraine.

Form lines . Landing strip . Tailings pond . Well (other than water); windmill. 0 t SUBMERGED AREAS AND BOGS Water tank: small; large. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .. • @ VEGETATION Marsh or swamp . Other tank: small; large. • @ Woods.

SUbmerged marsh or swamp.

Covered reservoir . @~ Scrub.

Wooded marsh or swamp. Gaging station . Orchard SUbmerged wooded marsh or swamp… Landmark object . o Vineyard.

Rice field. Campground; picnic area . I 7<' Mangrove..

Land subject to inundation.

Cemetery: small; large .

FIGURE 6.10 Standard symbols on USGS maps. Source U.S. Geological Survey

104

Chapter 6 Topographic Maps and Digital Elevaton Models 105

x26 as here, the vertical and horizontal x x 15 x15 25 scales are different. In Figure 6.l2C, x20 2~ / the horizontal scale is about I” equals 23 x 800′ (1:9600) whereas the vertical x 20 15 x 15 x x / 20 scale is 1″ equals 160′ (1:1920). If the x x 10 x 10 x scales were the same, the profile 15 x x 5 / x 15 would look flat.

Use of an expanded 10 5 10 x vertical scale highlights (exaggerates) x 5 5 topographic variations. 4. Transfer each mark made along the A. B. profile to the appropriate place on

FIGURE 6.11 the graph paper by aligning the How to make a contour map: A. Elevations from numerous transects across the area are added to paper with your graph (Fig. 6.12C). a sketch map. B. Smooth contour lines connect the dots at the elevations corresponding to the Mark the ends of the profile on the contour interval. Lines are smooth except where they cross drainages. graph paper.

Mark the contour and stream points on the graph at their appropriate elevations. This is done by going straight up from the mark y on the paper (or, as illustrated here, down from the top of the graph paper with the marks made directly on it) to the horizontal line repre- senting the same elevation; make a small dot on the paper at this point. 5.

Connect the points on the graph paper with a smooth line represent- A. ing the topography (Fig. 6.12C).

When crossing a valley or a hilltop, there will be adjacent marks with the same elevation. Instead of connect- ing them with a straight line, draw your profile line so it goes up over a hilltop or down into a valley. In the case of a stream valley, the low point in the valley will be where the stream crosses the line of profile.

Vertical Exaggeration of Topographic Profiles Profiles are commonly drawn with a verti- cal scale that is larger than the horizontal I i I i I I I I I I i i I i i i I scale. This vertical exaggeration reveals X~ 0 00 ~Y 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 co co c;o 0 co c;o E c;oco 0Cj ~ 0 ‘t co co 0) 0) co Cll coco co co 0)0) topographic features that otherwise might ~

1000 ,—;.–+–+-+–+—;—-;—–+—“>–+-;–+—;..->–.—+,———–,1000 not show up on the profile. The amount of vertical exaggeration is determined by the

— ratio of the horizontal map scale (for

900 1–+-+—+:-./—=”‘=”-:::_ _ :—+——‘f——t—-…;–+–7:/—,1:”–/—+—-1900

:./ :/ :/ –:/ FIGURE 6.12 Construction of a topographic profile. 800 f – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – j f – – – I 8 0 0 A. Choose a line of profile (X-Y). B. Mark intersections of contours and the stream, and note elevations on paper laid along the profile line. C. Choose a vertical scale, and transfer x y the points from the previous step to the appropriate elevations. Connect the points c. with a smooth line to complete the profile.

–~—– – – —- . ———-

106 Part III Maps and Images

950 Gradient .~. Gradient represents the change in eleva- tion over a specified distance and often 900 …– A is expressed as feet per mi Ie or meters <{ • .Q ………. .. -L-.I" …….. – per kilometer. The greater the gradient,

—- Q) (ij ~ ~ ./ the steeper the slope and the more

—- o (/) 850

830 – ./’ /’ ~ …………. ~ ~- . -“‘- / ./ !-

i_ closely spaced the contours. A gradient

of 10 feet/mile means that the elevation of a gi ven point is 10 feet higher than it is a mile away downhill. On a contour x y map, gradient is determined along a line or stream course by (I) using contour

FIGURE 6.13 lines to determine the difference in ele- The profile from Figure 6.12 is shown using three different vertical scales. The horizontal scale is vation between two points, (2) using the I inch to 800 feet. In profile A, the vertical scale, shown in yellow on the left side of the profile, is I inch to 80 feet, so the vertical exaggeration is 800/80 = LO times.

In profile B, the vertical horizontal scale to determine the dis- scale, shown in purple on the right side of the profile, is 1 inch to 160 feet, so the vertical tance between the same two points, and exaggeration is 800/160 = 5 times.

In profile C, the vertical scale, in red, is I inch to 800 feet, so (3) dividing the vertical difference by the vertical exaggeration is 800/800 = I times-there is no vertical exaggeration. the horizontal distance. For example, if the elevation along a stream changes 60 ft in a distance of 7.6 miles, the gradi- ent is 7.9 feet/mile (60 feet divided by 7.6 miles).

Note that in the case of a stream, the distance is measured along —-f——–~t::—–l—– the stream itself; it is not the straight-

Relief ___ 1_ __ Elevation line distance between two points (unless the stream is straight).

Height and Relief If someone asks you what your height is, you would say something like 5 feet 9 inches. This is the distance from the floor to the top of your head. You can also talk about the height of a hill, which is the difference in elevation between the top of the hill and the bottom.

A related but different term, relief,

FIGURE 6.14 refers to the difference between the This profile view shows that the elevation of the hill on the right is measured from sea level, highest and lowest elevations in a given whereas its height is the difference in elevation between the top and bottom of the hill. Relief is area.

For example, in Winnebago the difference in elevation between the highest and lowest points in a specified area, such as the one that is outlined. County, Wisconsin, the highest elevation is about 920 feet, and the lowest is about 745 feet.

Therefore, the relief of the example, I” to I mile) to the vertical scale 1″ horizontal = 5280′ = 33 county is 175 feet (920 – 745 = 175 ft). on the profile (for example, ~” to 20′). 1″ vertical 160′ In Jefferson County, Colorado, inunedi- To calculate the vertical exaggeration ately west of Denver, the highest and The vertical exaggeration is 33 times of a profile, first convert the horizontal lowest elevations are approximately (33X).

This means, for example, that the scale and the vertical scale of the profile I 1,700 feet and 5100 feet; the relief is distance representing a vertical difference to the same units. For example: 6600 feet.

Relief is also used in a rela- in elevation of 25 feet on the profile tive sense: a mountainous area has high The horizontal scale is 1″ to 1 mile, would represent a horizontal distance of relief whereas a plain has low relief.

Jef- which is the same as I” = 5280′. 25′ X 33 = 825′ on the horizontal scale. ferson County has high relief and Win- The vertical scale is ~” to 20′, which is Figure 6.13 shows the profile from Figure nebago County has low relief. Figure the same as 1″ = 160′ (= 8 X 20′). 6.l2C exaggerated (A and B) and non- 6.14 illustrates the differences among exaggerated (C).

Note that an exaggera- Next, divide the number of feet per elevation, height, and relief. tion of 5 X was chosen for the profile in inch in the horizontal scale by the number Figure 6.12. of feet per inch in the vertical scale:

I Hands-On Applications

You are probably already familiar with maps used to display roads and political boundaries. The hands- on exercises that follow develop the basic skills needed to use and interpret the information-rich topo- graphic maps. As you will see throughout this lab manual, such maps are essential for recognizing and understanding the character, origin, and even future of many landscapes.

You will also see how geo- logical data, when plotted on maps, can clearly present a picture that is difficult to see without a great deal of field work. Learn well the skills in this chapter, for they will serve you over and over again throughout this class.

You will also draw upon these skills if you choose a career dealing with any aspect of the Earth’s surface (e.g., in geology, environmental remediation and planning, land use plan- ning, archaeology, biodiversity and ecologic assessment, resources management, parks and recre- ation, civil engineering, etc.).

Objectives If you are assigned all the prob- 6. Number the sections of a direction of stream flow, and lems, you should be able to: township if they are not already locations of hills and valleys. numbered on the map. 13. Determine the contour interval 1. Define latitude and longitude. 7. Determine the scale of a map and of a map. use it to measure distances. 14. Make a topographic map using 2.

Describe the boundaries of a quadrangle map in terms of 8. Convert among verbal, fractional, points of elevation to draw latitude and longitude, and and graphic scales. contour lines. locate a point on a map using 9. Give the magnetic declination of IS. Construct a topographic profile these coordinates. a map (assuming it is printed on and determine its vertical 3.

Locate a point using the the map) and explain what it exaggeration. Universal Transverse means. 16. Detennine the gradient of a Mercator (UTM) system. 10. Determine what the various stream using a topographic map. 4. Locate or describe a parcel of symbols used on a map mean land using the U.S. Public (symbols for streams, roads, Land Survey System, and houses, etc.). give its area in acres. 11.

Use a contour map to determine S. Give the dimensions and area elevation, height, and relief. of a section and township (in 12. Use the characteristics of contours miles and square miles). to determine steepness of slope,

Problems 1. The basics of USGS topographic maps: Examine the map provided by your instructor to answer the following questions. Tables to convert between different units are found inside the back cover. Show any calculations you make. a. What is the name of the quadrangle and in what year was it last published or revised?

b. As frequently happens, you become interested in a feature that goes off the map. What are the names of the quadrangles to the east and southeast?

107

– – —-~——— ~-

108 Part III Maps and Images

c. What is the northern boundary latitude? Western boundary longitude?

Southern boundary latitude? Eastern boundary longitude?

Subtract these latitude and longitude numbers to get the size of the quadrangle in units of degrees, minutes, and seconds. d. What is the fractional scale of the map?

Determine the approximate verbal scale: I inch = miles. As always, show your calculations.

An environmental restoration project requires that you enlarge part of the map to a scale of 1 inch to 1000 feet. Calculate the factor by which it needs to be enlarged.

What would the enlargement factor be if you needed a scale of 1 em to 100 m? Hint: Start with the fractional scale.

e. What is the contour interval?

f. What is the highest elevation within the area designated by your instructor?

What is the lowest elevation in that area?

What is the relief of the designated area?

g. What is the height (not the elevation) of the location designated by your instructor?

h. Give the elevation of the location designated by your instructor.

I. Determine to the nearest minute the approximate latitude and longitude of the designated feature.

j. Determine to the nearest 100 m the full UTM coordinates of the designated feature.

k. If the map is subdivided by the Township-Range method, locate the feature designated by your instructor to the nearest Y,6th of a section.

I. What is the approximate size of the area designated by your instructor (in acres, if subdivided by the Township-Range method, in square meters if the UTM method is preferred)?

m. Use the graphic scale to determine the distance in miles and kilometers between the features designated by your instructor.

n. In what direction does the water flow in the stream designated by your instructor?

o. What is the magnetic declination (in degrees) indicated on the map? In which year was this value measured?

Chapter 6 Topographic Maps and Digital Elevaton Models 109

2. Analyze a landscape: Let’s say that you’re a developer with a big project in mind for an area near Averill, Vermont (Fig. 6.15). You first need to study a topographic map to understand the landscape. Show any calculations you make for the following questions. Conversion factors are listed inside the back cover. a. Determine the following basic facts about the map:

Interval between index contours:

Contour interval (units in feet):

Fractional scale (Hint: Use the UTM grid and metric units.):

Verbal scale (I inch = miles):

Approximate height and width of the map. (Hint: Use the UTM grid as a bar scale.)

Approximate height and width of the map in miles (Hint: Use the verbal scale and a ruler.):

By what factor was this map enlarged or reduced from its original 1:24,000 scale?

b. To get a feel for the landscape, find the three most prominent mountains rising above 2200 feet. List their elevations starting with the mountain near the top of the map and going clockwise. The “T” following the bench mark elevations means they were determined from air photo measurements, which have errors of a few feet relative to the more accurate method of surveying.

c. Determine which way the streams flow by looking at how the contours are deflected as they cross them. Draw arrows showing the flow directions of the streams flowing into or out of the ponds and lake.

Which ponds or lakes flow into each other? (You can double-check your inferences by noting water level [WL] elevations.)

Use the stream drainages to help you find the lowest elevation on the map. What is this elevation?

What is the total relief of the map area?

Let’s say that you plan to hike up Brousseau Mountain from a canoe beached on Little Averill Pond. What is the height of Brousseau Mountain relative to this starting point?

d. At the top of Brousseau Mountain you plan on checking your hand-held Global Positioning System (GPS) unit to be sure it works. Note that UGSG maps show latitude and longitude divisions no finer than 2′ 30″ (see left map margin), so you have to switch your GPS unit to UTM coordinates. Use the map to determine the UTM grid coordinates you expect to see when you reach the peak of the mountain (marked with an elevation on the map).

e. Because your development plans include golf courses, a water park, factory outlet shopping, and extreme paintball, you need quite a bit of land around the Averill ponds. Do the little black dots on the map represent anything relevant to your development plans? Explain.

(

FIGURE 6.15 Portion of the Averill, Vermont, 7 ~-minute quadrangle map for use in Problem 2. Canada is just a few kIn north of the map area. Scale and contour interval are determined as part of Problem 2.

110

Chapter 6 Topographic Maps and Digital Elevaton Models III

o ————-.—————————–..——-..——–..——–.—————————.—————————-.—————–.————————————.————————–.—————-.————————– 55—————————————————–.-.– CJ … —- ..-….. —– .. — …. ——————————————– ————-.– •••••••• -•• -••• -.-.-.———.——- ••• ——–.——- •• ——– •• ——- •• ——– •• ——–.——– •• ——–.——– •• —— •• ——- •• ——–.– —– •• ——–.——- •• ——–.——–.——–.——- •••• ——-.——-

o —- — ——.——–.-.– – –.–.- -.—- – —– -..—……….. —-.- – ——-.— – —- . 8- —.————- .. –.—— -.. ———————————————————————————————— CJ •••••••••••••••••• -••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••• -.—.—.– •••••••• -•• -••• —————-.– •• —-. ——–.——–.-.——.——– •• ——- •• — •• -••• ——–. ——– •• — •••••••• -•••••• —————- •••••••• -.- ••• —

o 55 …….- – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – ‘ ~A A’

FIGURE 6.16 Blank graph for constructing the topographic profile of Problem 2. The vertical axis marks feet above sea level.

f. Being a developer of taste and refinement, you’d like to put your name in 20-foot-tall neon letters on the top of Brousseau Mountain. But will your guests be able to see your name from the lodge dining area to be located at point X on the map? To find out, construct a topographic profile along the line A-A’ on Figure 6.15.

To save time, use just the index contours except when marking the elevations of hilltops and valley bottoms. Draw your profile on the graph provided (Fig. 6.16). Label “Brousseau Mountain,” “Great Averill Pond,” and “Black Brook” on your profile. Draw a 20-foot letter on Brousseu Mountain and see if there is a direct line of sight from point X (the future dining room) to the letter.

Will the guests be able to see your name in lights?

What is the vertical exaggeration on the profile you drew? Show your work.

3. Comparing a contour map with a DEM: Figures 6. J 7 and 6.18 show the area around Mono Lake, CA. Use these figures to answer the questions that follow. a. Determine some basic facts about the map (Fig. 6.17): The contour interval is 200 feet. In low-relief areas, such as in Mono Valley, they have inserted supplementary contours (dashed). What is the elevation difference between a supplementary contour and an adjacent regular contour?

Older USGS maps often emphasize the Township and Range grid system; newer maps often emphasize the UTM grid. What is the name for the areas outlined by the red squares, which are marked by such labels as R27E and T3 ?

About how many miles separate adjacent red lines on this map?

Maps of western states frequently show many mines (most are small and abandoned) and many springs. Draw the symbols for mines and springs as shown on this map:

Why might mappers of western states be concerned with showing every spring they find?

b. Because I:250,000 maps cover a lot of area, their contours tend to show only larger features. The USGS sheets also tend to be cluttered and difficult to read. In contrast, the OEM of Figure 6.18 clearly shows even subtle landscape features. The OEM image was compiled from a series of OEMs derived from the standard USGS 7Y,-minute topographic quadrangle maps. Comparison of Figures 6.17 and 6.18 makes obvious two advantages of OEMs: They are free of non-landscape

112 Part III Maps and Images

FIGURE 6.17 Portion of the Walker Lake (north half) and Mariposa (south half), CA, I° by 2° quadrangles for use in

Problem 3.

Original scale 1:250,000 C.1. 200 feet

clutter and, because they are based on the highest resolution maps available, they can show both broad features and fine detail, even when covering a large area. Use Figures 6.17 and 6.18 to answer the following questions: Only fresh water flows into Mono Lake, but Mono Lake itself is very salty. Why is this? Hint: Do you see any stream leav- ing Mono Lake?

Since 1850, lake levels have fluctuated between 6428 feet (1919) and 6372 feet (1982). Has Black Point been an island at any time since 1850?

Chapter 6 Topographic Maps and Digital Elevaton Models 113

FIGURE 6.18 A digital elevation model (DEM) of the area around Mono Lake, CA. Lowest elevations are deep green, highest elevations are yellow. The lake level is set at 6382 feet, which is typical for the years 2000 to 2004.

Original scale 1:250,000

Lake levels have always fluctuated naturally, but from 1941 to 1982 the lake levels consistently dropped as the thirsty city of Los Angeles siphoned off more and more water from the mountain streams that feed the lake. As the supply of fresh water was cut off, how do you think the concentration of salt in the lake changed? Explain.

Los Angeles is now restricted in how much water it takes in order to preserve one of the most productive ecosystems in the world. A host of inveltebrates in the lake feeds 84 different species of water birds, including 50,000 nesting California gulls! c. Can you see anything in the DEM suggesting that lake levels were once, before 1850, considerably higher than they are today? Describe what you see and why your observations seem to be connected to lake level.

114 Part III Maps and Images

What you are seeing are called lake terraces. Lake terraces form when the lake stabilizes at a certain elevation for long enough for its waves to erode a little notch into an otherwise smooth slope. From an airplane you can see many more terraces that are too small to show up on topographic maps and therefore DEMs.

It can be difficult to date lake ten’aces, but it turns out that during the last ice age (125,000 to 10,000 years ago) there were large lakes all across the deserts of the western United States. Even Death Valley, CA, had a lake in it. What does this say about the climate of the western deserts during the last ice age as compared to today?

d. An experienced geologist looking at Figure 6.17 also sees evidence for glaciers flowing to the shores of Mono Lake from the Sierra evada Mountains to the west, for volcanic activity in the hills south of Paoha [sland, and for at least two possible faults cutting across the area. If DEMs are such amazing sources of insight, why do we still use contour maps?

The following question addresses this issue. Let’s say you need to do some sort of field work on private land near Cottonwood Canyon north of Mono Lake. You need permission to access the land, you need to know how to get to the land, and you are working in a desert. Name at least three things the map gives you that the DEM does not.

With Geographic Information Systems (GIS) software you can automatically generate topographic profiles, obtain elevations of specific points, and superimpose roads, vegetation, and other information on your DEM. Thus, the DEM can become like a super topographic map, and the GIS software can help you do many tasks (e.g., calculate past lake volumes) that would take hours to do by hand.

However, for detailed work, people still often superimpose contours on their DEMs. Thus, what you have learned in this chapter has not been made obsolete by modern software. Instead, you have learned the fundamental needed to effectively operate GIS software. 4. Do-it-yourself map: Let’s say you are a famous architect.

A wealthy client who made her fortune eating live parasites on TV wants a 5000-square-foot “cottage” built on a plot of heavily forested land featuring a babbling brook with a waterfall and some river front. She wants views of both the waterfall and river.

The problem is that the existing 7Y,-minute topographic map does not show enough detail to allow you to pick a building site that offers both views. You therefore send your trusty assistant to do a topographic survey of the area. She makes a number of uphill transects across the property and carefully marks on a map the position of each 5-foot increase in elevation (Fig. 6.19).

Since the river was dammed to make a reservoir, each transect starts at the constant elevation of the river shore. Unfortunately, your assistant quits, and you are left to draw the contours on the map so that you can answer your client’s questions. a. Draw the contours on the map (Fig. 6.19). Use a contour interval of 10 feet. Many of the 5-foot increments were omitted for clarity.

Your assistant, recognizing a great site for the house, had circled a small hilltop with a 40-foot contour line.

Don’t forget how contours are normally deflected as they cross drainages. b. Label the waterfall on the map. Explain whether it appears to be a single vertical drop or a close series of cascades. What is the minimum vertical drop over the run of this waterfall/series of cascades?

c. Your assistant fortunately wrote the scale on the map. Measure the length and width of the area inside the 40-foot contour encircling the 42-foot elevation point. Assume that a rectangular house of these dimensions could be built on this hilltop. [s the hilltop large enough to accommodate the 5000-square-foot cottage that your client needs to entertain her fans and admirers?

Chapter 6 Topographic Maps and Digital Elevaton Models 115

+55 +55 50

+55 +50 +45 +50

~ +50

40+ +45

35 +45 30 +55 +++20 40 15+ +45 + ~ ~~10 +50 50 +40 + +45 40+ +30 +20 +45 +0 +10 +30 + +40 +20 5 +35 +10 +5 +30 +5 +20 ~O Scale = 1:8,400

FIGURE 6.19 Elevation data for drawing topographic contours (Problem 4). One contour has been drawn for you. North is up.

Maps on the Web 5. Sample a national parks map: Go to www.lib.utexas.edu/maps/national parks.html (or link to it through www.mhhe.com/jones6e-see Preface). Select Devils Tower National Monument [Wyoming] (shaded Relief Map) and answer the following: a. What is the elevation of Devils Tower? b. What is the contour interval of the map? c. What is the approximate height of Devils Tower? d.

What is the top of Devils Tower like? Is it jagged, flat, or dome-like? e. What does the dashed line that more or less circles Devils Tower appear to represent?

f. Let’s say you wanted to hike to the top of Devils Tower. Is it too steep? We can get the vertical distances from the contour interval, but unfortunately no scale is given on this map. Another source indicates that the maximum distance from the west to the east side of the tower top (the 5100-foot contour) is about 180 feet.

You can see from the map that the horizontal distance between the 5100- and 4600-foot contours on the north side of Devils Tower is also about 180 feet. Thus, on the north side the elevation changes about 500 feet over a horizontal distance of 180 feet.

What is the gradient (in vertical feet per 1 foot horizontal)?

—–~ .- _ – “-“— -=—–==—=—-=- – – – – –

116 Part III Maps and Images

g. What angle does this surface make with respect to the horizontal? Use the following graph to sketch the gradient you just got and either measure the angle with a protractor (less accurate) or use trigonometry to calculate the angle (more accurate). Label your graph.

If you were on a roof pitched at this angle, you would find it very difficult to keep from slipping off. Thus, you would have to be a rock climber to scale Devils Tower.

Devils Tower is an interesting place. If you want to see what it looks like, try going to den2-s11.aqd.nps.gov/grd/parks/deto/index.htm (or link to it through www.rnhhe.com/jones6e). Climb the Tower: A web search reveals numerous sites dedicated to climbing Devils Tower. It’s a classic place for technical rock climbing.

A National Park Service website (www.nps.gov/deto/home.htm) gives some information on historical climbs of the Tower (before the advent of modern equipment) as well as its geology (click on “Study the Tower”). 6. Topographic maps and DEM data on the web: If you need a map, DEM image, or air photo of a given area, there are many available web resources.

Here is a brief guide to some we’ve found useful: o TopoZone (www.topozone.com) delivers map portions centered around the place or coordinate you specify. You can see your area on maps of scales of I :24,000, I: 100,000, and 1:250,000, and you can see different areas at each map scale by adjusting the scale at which the map is shown on the screen.

A “print” link allows you to print or save your map. o Terraserver (terraserver-usa.com) has a map interface that isn’t as good as TopoZone (you don’t know what scale maps you are looking at), but you can switch to an air photo view of your selected area. o Sam Wormley’s GIS Resources (www.edu-observatory.org/gis/gis.html) lists site links that carry scanned USGS topographic maps.

Look under “DRG’s Available Free Online”; DRG stands for “digital raster graphics.” The disadvantage of full maps is they are larger files and are difficult to print unless you have a large plotter. o MapMart (www.mapmart.com) allows you to download USGS DEM files for 7 ~-minute quadrangles.

You can easily learn the name of the quadrangle you need by typing a place name into TopoZone’s search engine. A good MapMart interface allows you to zoom in on the quadrangles around your point of interest and to quickly and easily download (for free) the DEM files.

Note: You will need specialized software to see these DEMs. o OEM software resources (edc.usgs.gov/geodata/public.html): To view DEMs, you’ll need software that

translates the SDTS-format files the USGS provides. This page lists some freeware and shareware programs that you’ll need to download and learn to view DEMs.

MacDEM (www.treeswallow.com/macdem) is a nice shareware program for the MacIntosh. dlgv32Pro (mcmcweb.er.usgs.gov/drc/dlgv32pro/) is a nice freeware package for pes. o United States Geological Survey Publications Page (www.usgs.gov/pubprod/) lists publications (including maps) and tells you how to purchase them.

There are links to many on-line retailers of USGS maps (click on Retail Sales Partners to get to an alphabetical list). o You can easily check out all these links by visiting a single web site: www.mhhe.com/jones6e.

Chapter 6 Topographic Maps and Digital Elevaton Models 117

7. Where is the magnetic north pole today? Magnetic north is always on the move. The Canadian Geologic Survey has set up a nice website (gsc.nrcan.gc.ca/geomag/nmp/northpole e.php) showing the magnetic north pole’s current and past positions on its journey through northern Canada. It explains why variations occur on daily and yearly time scales and projects the future locations of the magnetic north pole. It is worth taking a moment to check out this web site.

In Greater Depth 8. Plan a hiking excursion: British Columbia offers some of the most rugged scenery in North America. If you like hiking, leafing through a stack of Canadian topographic maps will inspire daydreams of amazing wilderness experiences (if you avoid the many logged out areas, that is!).

Figure 6.20 shows a portion of the Wells Gray Provincial Park in central BC This park is in the Cariboo Mountains, which are part of the Columbia Mountains. The blue lines and numbers define the I-km UTM grid. The map symbols are similar to those of USGS maps (Fig. 6.10); the actual map key is handily printed on the back of the original map.

Let’s say your goal in visiting this part of the park is to combine geologic exploration with back-country hiking. To get there, you portage 13 km from a lake to the south and paddle some 25 km until you reach the end of Hobson Lake, the large lake shown in the southwestern corner of Figure 6.20. For more information and photos, visit www.wellsgray.ca. a.

First off, most of the map area is covered in green. What does this mean?

b. Your goal is to climb the large hill with a number of lakes on its top (near “FP GP”). What is a representative elevation of the area with the many small lakes? What is the height of this area relative to the lake that you arrived on?

c. To get to this hilltop, you need to beach your canoe and hike. Based on the map symbols, what is the landscape like at the northeastern end of the lake?

Do you think it would be an easy hike across such a landscape? Why?

d. The edges of established forests, such as along lakes or highways, often SpOt1 a dense undergrowth. Away from the edge, the undergrowth tends to disappear and hiking is easier. In anticipation of this and other problems that can effectively block a path, use the following guidelines to draw three possible paths leading to the lake area on top of the hill.

Label each path l o Path A: Take the shortest route from the lake shore to the hillside. Continue to the hilltop with the lakes via a route that, while it may be long, follows the gentlest slopes.

The goal is to avoid scaling a cliff. o Path B: Take the canoe up East Creek (which drains into Hobson Lake) and land where you won’t have to worry about marching through a swamp and where you get the most direct route to the lakes without climbing unnecessary elevation. What is the average slope of your path once it starts up the hill? Express the result in meters per meter.

o Path C: Take the canoe up Hobson Creek as far as necessary to avoid swampy land and to gain access to the gentler slopes leading to the toe of the hill near the letter “I.” Avoid any closely spaced contours that indicate inconveniently steep slopes, and avoid climbing unnecessary elevation on your way to the lakes on the hilltop. Calculate a typical slope of this path once it starts up the hill from near the letter “1.” Express the result in meters per meter.

e. Find the peak with the highest elevation on the hill with lakes and mark it with an “X.” What is its elevation?

118 Part III Maps and Images

f. Cliffs offer good rock exposures, possible great rock climbing, and nice places to sit for lunch. There are two prominent cliffs on the north side of the hill with lakes. Mark the taller one with an encircled exclamation point (!). Estimate the height of this cliff by reading the contours that fall between the breaks in slope at the top and bottom of the cliff.

g. Finally, one might expect to cover 10 to 20 km per day on a hiking trail. Let’s assume you can make 10 km a day in this rugged wilderness. Assuming you take trail C, how many days should you plan for in reaching the highest point of the hill, exploring a bit, and getting back down to the canoe?

FIGURE 6.20 Portion of the Hobson Lake, Be, quadrangle map for use in problem 8. I:250,000 scale. Elevations are in feel.